Psychology & Physiology

Summary

4/26/2025 Read time 5 min.

Crossing the Atlantic is an incremental addition of risk to your operation. Decide beforehand on your acceptable level of risk. Mine is an aircraft that is turbine-powered, pressurized, has anti-ice capabilities, and has no ferry tanks. YMMV.

Fatigue is the real danger on a sustained mission. Arm yourself with a plan to combat fatigue beforehand.

Details

Golden Age

The first transatlantic crossing by an airplane happened in 1919, just 13 years after the Wright brothers flew. The US Navy commissioned three Curtis flying boats to cross the Atlantic. Of the three, one completed the crossing, NC-4, under Commander Albert Read and his crew of six. It took five legs and 24 days to fly from New York to England. There were many mechanical setbacks and delays. To put it in perspective, at the time, a modern-day ocean liner could cross the Atlantic in five days, carrying 1500 to 2000 passengers. So, while it may be hard to call this a success, it was definitely an accomplishment.

Perhaps inspired by the Navy's feat, that same month, a businessman named Raymond Orteig announced a $25,000 ($460,000 in 2025 dollars) prize to any Allied country citizen who could fly from New York to Paris nonstop. It wasn't until another eight years later that Charles Lindbergh completed the mission.

Lindbergh commissioned Ryan Air to build the Spirit of St. Louis for $10,500. It took two months to build, and 10 days after production, it was declared fit to cross the Atlantic. Due to its range, it flew from California to New York City, setting new speed records.

The Spirit of St. Louis had a 450-gallon tank that sat right in front of the pilot and required a periscope to see over the nose of the airplane. It had a compass and basic dead reckoning instruments, rumbled along at 100 knots, burned 10 gallons per hour, and had no radios or extra seats to save weight. The St. Louis took off from New York on its journey. It was well over gross weight, barely cleared the telephone lines on takeoff, and slowly began the 3200 nautical mile trip to Paris.

Over the Atlantic, Lindbergh encountered icing, experienced hours of complete isolation, and was so fatigued that he began hallucinating and had to mechanically prop his eyes open to stay awake. Despite the challenges, he made landfall within 3 NM of his planned route. When he was spotted over Ireland, advance notice was sent to Paris, where 150,000 persons greeted him upon his night landing. The flight took 33 1/2 hours. Lindbergh was awake for 63 straight hours from preparations until retiring to bed in France.

At this time, aviation was rapidly advancing. In the following year, Amelia Earhart completed her first Atlantic Crossing as part of a crew of three in 20 hours and 40 minutes. Her more famous crossing in 1932 was the first woman's transatlantic solo flight. It was also the first solo flight since Lindbergh’s. She left Newfoundland, Canada, and flew to Ireland. The 1700 nautical mile journey took 15 hours in her Lockheed Vega, traveling at 130 knots.

Early aviators and legends kicked off the golden age of aviation. There's a rich history and an ethos in aviation. How this new technology was to connect Western civilization was yet to be determined. These early aviators were adventurers, risk-takers, pioneers, and survivors. Before Limburg's success, six other well-known aviators lost their lives attempting to do the same. And while Amelia survived the Atlantic, she went down and died in the Pacific attempting an around-the-world flight in 1937, only nine years after the first Atlantic crossing.

Ninety years later, crossings are routine and safe. Hundreds of flights and thousands of passengers safely travel between the continents. New York to Paris now takes 7 1/2 hours. We have a highly organized system across the Atlantic, building new highways in the sky every day.

Psychology

So you have to ask this question: why would you want to do this yourself? Why not just take an airline? After all, it's quicker, cheaper, less hassle, and less risky. On the other hand, we're not talking about taking an untested, experimental, radial engine aircraft with no anti-ice, pressurization, radios, and only rudimentary navigation equipment into unknown weather under no surveillance. We have all these advantages in modern equipment that lower the bar considerably.

There are other, more spiritual reasons for making the flight. You are tapping into the history and adventure of aviation, your personal growth, and your broadening experience. Desiring a challenge or a taste of adventure is what got most of us involved in aviation in the first place.

I've completed 11 Atlantic crossings in the PC-12. The elephant in the room is that it's a single-engine airplane. "You're crazy to fly over water with only one engine! If that engine goes, you're dead. That's neat, but I wouldn't go unless I had two engines." - Maybe. Probably. Would you?

Flying is an inherently risky thing to do. We are flying an aluminum pop can with thousands of pounds of flammable fluids, lighting it on fire, flying hundreds of knots per hour miles opposed to the force of gravity into freezing and unbreathable air. Most of the risk has already been taken by getting into an airplane, no matter what you're flying over. Terrain or oceans add an incremental risk on top of that. As Lawrence Gonzales says in his book Deep Survival, reflecting on the condition of all humanity, "You're already flying upside down; you might as well turn on the smoke and have some fun."

But how risky is it? When you consider risk, you have to consider the likelihood that something will happen and the severity of the consequences. Going down the ocean is a severe consequence, but when you consider the likelihood, at most, you're taking a moderate level of risk.

Let's dig deeper and quantify the probability of an accident.

Business aviation has an accident rate of about 0.75 per 100,000 hours. That number drops to 0.19 accidents per 100,00 hours for a two-pilot crew. But if you assume the higher rate, it takes about 133,000 flight hours for one accident. If it's about nine hours per Atlantic Crossing in the turboprop, we may see one accident every 15,000 crossings. The rate of accidents during cruise (unable to glide to shore) is 10 to 15% of all accidents, raising the accident rate to one in 100,000 crossings to achieve the dreaded ditching situation.

Since the biggest concern is engine failure, we must dive deeper into the details. A PT-6 has a total power loss rate of 1.6 occurrences for every 1 million hours, or put another way, one occurrence per every 625,000 hours.

If you calculate the distance and time you are outside the gliding distance of land, it comes out to about 1000 nautical miles at PC-12 speeds, or about 3.8 hours of risk of a wet footprint.

Based on that, we can expect one total power loss outside of gliding distance over about 165,000 crossings. That's like crossing the Atlantic once per week for 3100 years - the beginning of the Mayan calendar.

Despite the low probability, two PC12s have gone down in the ocean in the last 25 years! Although I would like to avoid being a Monday morning quarterback, based on conversations with those in the know, it appears that at least one of these ditchings did not have to happen.

Antedationally, looking at the actual occurrences, the odds of successfully ditching in the ocean are pretty good. One accident had a minor injury, and the aircraft floated in the water for 4 1/2 hours after ditching. They had proper survival equipment and were picked up via ship. Based on the data, it's extremely unlikely to encounter the dreaded scenario of ditching in the water, and the severity isn't as bad as we imagined it to be.

No, the elephant is a red herring. The real danger is fatigue.

Physiology

You will undoubtedly be fatigued if you complete a crossing. The long legs, multiple time zones, constant vibrations, and additional mental load all add up. As a human, you have limitations on performance. You can only stay awake for so long and perform at a high level for less.

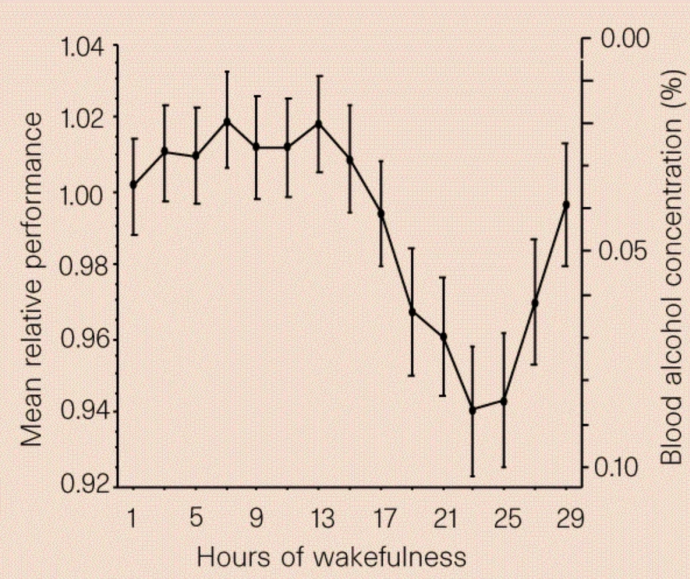

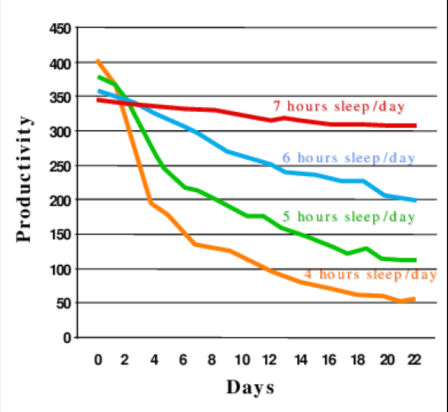

Comparing hours of wakefulness vs. blood alcohol concentration, approximately 16 to 18 hours of wakefulness equate to .04 blood alcohol concentration. Twenty-two hours, and your performance degrades to a .08 BAC. Here is the key: that is all for day one. Days two, three, and four are where fatigue accumulates, performance plummets, and you make mistakes.

“There are no solutions, there are only tradeoffs.”

Acute Tools

One way to combat fatigue in the short term is with caffeine, but caffeine is essentially the energy loan paid back with interest, so it takes some management. It's best to let your body drag while in cruise, and then at the top of descent, have a half a cup if you need it. This will bring you to alertness, hopefully not disrupting sleep too much.

Hydration is another way. It only takes a 1.6% reduction of fluid loss to cause fatigue. That's about 2 lbs of water for a 200 lb person. You lose about 5 lbs (80 oz) of water daily. Day one won't have much effect, but days two and three begin to compound if you're not keeping up.

A second crew member is huge. The ability to unplug and rest for a bit, to stand up and stretch, and to have additional eyes to trap mistakes will help tremendously, as the previously mentioned accident rate indicates.

Unfortunately, alcohol has a detrimental effect on our fatigue levels. As interesting as it can be to sample local libations, there is a cost. It only takes two alcoholic drinks to decrease sleep quality by 24%. Combine that with staying in an unfamiliar hotel bed and jet lag, and you can quickly lose hours night after night.

Long Term Planning

I know what you're thinking: " Yeah, duh, you sound like my mother." I cannot explain with words how sneaky and insidious fatigue is, especially when you've probably gotten away with it many times. On a non-routine mission of crossing the Atlantic, you should make a plan and arm yourself with tools ahead of time.

“There are no bad decisions, only consequences.”

Leading up to the trip, build an itinerary with margin. From a fatigue and daylight perspective in a turboprop aircraft, a great schedule would be day one to get to the east coast, day two to Iceland, and day three to Europe.

During the trip, assume you are operating at a reduced capacity and intentionally slow down. Use the additional hassles of international travel (paperwork, language, etc.) to find a lower gear. There is no such thing as a quick turn internationally.

Once you are at your destination, adjusting to the new time zone can be accelerated using heat, food, and light - your three biological clocks that set your circadian rhythm. Check out Andrew Huberman's podcast on the subject for a detailed explanation. The cliff notes are:

When you warm up, you wake up. About two hours before you naturally awake, your body is in a low-temperature state. You can advance your biological clock by waking up in this two-hour window. Waking up before that low temperature slows your clock. Meaning a super early start to your day will work against you, and you will be more jetlagged.

Exercise will raise your core temperature and assist with wakefulness.

When you cool off, you sleep. A hot shower causes your body to expel heat and has a post-shower cooling effect, helping you induce sleep.

Eat like a local as soon as you arrive - schedule and cuisine!

The most significant influence on your clock is light. Getting sunlight as soon as you wake starts a 16-hour clock in your body to go to sleep later. Hence, fatigue levels rise at that mark. Conversely, avoid lights and screens when you want to sleep.

Adjusting your clock takes about a day per time zone.

In aviation, we break all the rules. We wake up early, sit sedentary for long periods, chug coffee, fly through the night in front of screens, eat what we can when we can, then fuel up and do it again. Many variables are out of control, but having a plan, an aim, and tools is much better than winging it.

Aviate

Decide your acceptable level of risk. Example: I will cross an ocean in an aircraft with a turbine engine with pressurization and de-icing capabilities and no ferry tanks.

Listen to the Huberman podcast.

Build a plan for sleep and fatigue management.

Navigate

Article 20 of 22 on your international operations journey. Eject at any time to land at international articles.